Exploring my ugly zone

Memories of my early white-water kayaking experiences consist of an overwhelming sense of not being in control. As a passionate mountaineer, I was learning to paddle because I needed a basic instructor ticket to work in the outdoor pursuits industry in North Wales.

I passed my 3 Star (a personal proficiency award) after just a few hours of practice. In those days, the 3 Star, an introduction to moving water, was trained and assessed on flat water. I learnt to ‘break-in’ to the current by paddling forwards on a lake, putting in a huge sweep stroke to turn my boat, then doing what I called an ‘air brace’ – a support stroke that was about as useful as a chocolate teapot! We practised these sequences and shapes every time I worked with a group on the lake.

My fellow instructors were all male and all experienced paddlers. The pressure to succeed as the only female shaped my perceptions and my determination to keep up with them. I felt that I had to be as good as, if not better than them, to survive in my work domain. I had to not make mistakes. And most of all had to be brave and show that, as a woman, I was capable of working in this industry. For their part, they thought that being generally confident and competent, I’d get along fine if they looked after me and I just kept trying.

A few early trips to the River Tryweryn in Bala were memorable for all the wrong reasons. I would be put in at the top of a section, told to follow the person in front of me and if in doubt, to ‘paddle like ***k’. On tricky sections, one of them would shout instructions to me as I paddled past them. The instructions were very technique focused. What to do. When. Never why? I was acutely aware of the fact that getting to the bottom, the right way up, had nothing to do with my ability. I was always too overwhelmed to be able to recognise or use any of the ‘affordances’ that the river features offered.

My boat, a classic old ‘micro-bat’ was basically a cork. Round edges meant that it bobbed along and stayed upright whatever I went through, or over. My little boat might have kept me upright, but it was not giving me good feedback about my paddling ability. This lack of direct feedback and consequence is what we call a ‘low validity’ learning environment. Sure, it kept me safe in water that was too hard for me to paddle. The downside was that it further reduced my chances of becoming skilful.

Unsurprisingly; the more paddling that I did, the less confident I became. The less confident I became, the more worried I got, and the more I would focus on what strokes and techniques I had learnt on the lake in my 3 Star. The problem with this, as I realised many years later, was that everything I had learnt when ‘breaking in’ on the flat lake was irrelevant to moving water. The current would turn my boat before I had even finished my sweep stroke, my air brace provided no support and all. My careful rehearsal was connected to an internal focus and making correct movement shapes – not to the information in my environment.

I don’t know if it was because I was the only female, but I was over supported and operating outside of my ability (what I now know as ‘controlling support’). This was not for any malicious reasons. I think that the boys genuinely thought I would be fine if they ‘looked after me,’ unaware that, like sitting idly in a passenger seat, I was not able to develop perception-action coupling or decision-making skills by just following and hoping.

Finding ‘search spaces’ for learning

Despite all of my previous experience mountaineering and being an active member of the local (Ogwen Valley) mountain rescue team, at that time I had also lost my confidence climbing and for exactly the same reasons as my paddling! All this changed with one day of winter climbing with a friend from the neighbouring Llanberis Mountain Rescue Team (LLMRT).

Nikki was a super skilled mountaineer and climber, and the first competent women I ever went climbing with. She was a team leader with the (LLMRT), an experienced search dog handler with the Search And Rescue Dogs Association (SARDA) and a ranger on Snowdon. The first thing that struck me was how she involved me in all the decision-making. Where would I like to go? What route? Which pitches did I want to lead? It seems crazy now to acknowledge the impact that had on me. The sense of ownership, excitement, and autonomy.

We romped up a frozen Idwal Stream in the Ogwen Valley, a relatively easy ice climb, taking it in turns to lead. Despite this being the hardest climb I had ever led, by the end of the route we were mostly soloing the pitches and then belaying the other up with a simple ice-axe belay. I had such a heightened awareness of the properties of the ice, placing my axes and crampons, belay points, making safety decisions. My focus was quiet and absolute.

We moved quickly and confidently together. My heart soared with the sheer exhilaration of feeling so confident about my leading ability. The thrill of being completely focused, absorbed, at ease, feeling totally respected and supported. It was a real turning point for me. I was still buzzing weeks later.

I vowed never to climb again unless I was leading, or at least alternate leading. It was a good decision. My confidence and ability grew exponentially.

(And no, this is not the ‘snow’ bit!)

The ugly zone

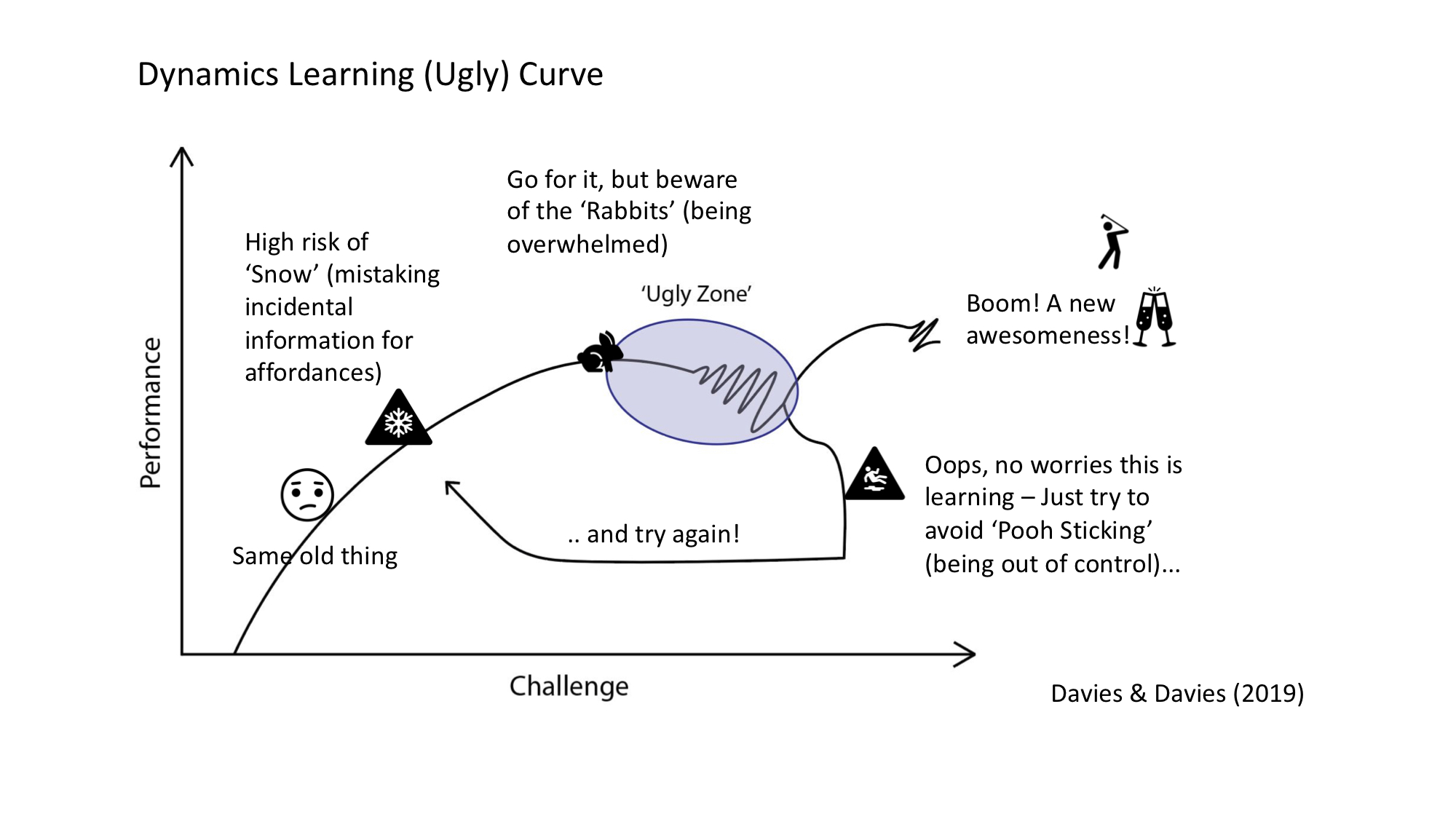

Now, I’m hoping that you are thinking the same thing as me about reflecting on these experiences. Mostly, that being in our ugly zone is a little more nuanced than just being out of our comfort zone!

As introduced in the ‘becoming skilful’ articles, the ugly zone represents the ‘search space’ in which we are able to become more skilful by developing affordances for action, through perception-action coupling. Although leading ice climbing pitches had a higher level of risk and consequence than paddling the Tryweryn, I was engaging with a totally different level of motivation, autonomy, perceptual and decision making focus.

Let’s have another look at the Ugly Curve and the important elements of Snow, Rabbits and Pooh Sticks.

Snow

Perception-action coupling to ‘specifying’ information

While we were co-writing an academic paper about developing adaptive expertise, Sam (my son) sent me a video clip about some early Artificial Intelligence (AI) experiments. This clip helped to outline why machines are not yet able to learn as effectively as humans. It was a TED talk by Peter Haas, sharing his experience of developing a Machine Learning algorithm designed to teach itself to differentiate between pictures of dogs and wolves. They presented the algorithm with training data by providing it with loads of pictures to analyse and also informing it as to which pictures were dogs and which were wolves. Then they started testing.

All went well until they came to the picture of a Husky. The algorithm said ‘wolf’. Curious, the programmers then re-wrote the algorithm to determine what information it was using to make the decision. Imagining the algorithm would highlight aspects of the Husky’s features such as ear shape, eyes or muzzle, they were quite shocked when it highlighted the ‘snow’ in the background of the picture. It turned out that most of the training pictures containing wolves had snow in them.

This error of association is very common for humans (and most other species). It is an associative learning bias. The important bit for us as coaches and performers is ensuring that we are learning movement solutions and decision-making based on ‘specifying’ information and not ‘snow’ that just happens to be in our training environment.*

How do we do this? Two key elements of the learning environment are important here.

1. Variability of the learning environment to reduce the likelihood of developing perception-action coupling to non-specifying perceptual information that just happens to be in one particular environment.

2. Ensuring that the learning environments contain the same specifying information as the performance environment. In other words, you use ‘Representative Learning Design’ (RLD) and variability in your practice.

My early kayaking practice on the lake, ‘pretending’ to be on moving water was a great example of ‘snow’. The environment was not variable and I had been encouraged to have an internal focus of attention on the shape I was making, not an external focus on specifying information in my environment (which did not exist on the lake anyway). This focus on non-specifying information meant in practise that I was biasing my focus of attention to irrelevant information when I was on a river. All of this was confounded by the pressure I put on myself, my lack of intrinsic motivation, and my anxiety about not being competent.

The motivational environment I was experiencing when I was paddling was not supportive of my basic needs (to have autonomy, relatedness and competence) so I was being thwarted in becoming more self-determined or skilful. My one day of ice climbing with Nikki was super-charged with self-determined motivation and learning, mostly due to it being a very needs supportive environment.

Rabbits

‘Worry’ taking up space in the ugly zone

A few years ago, I listened to a story online from a horse trainer called Warwick Schiller.

The basic gist of the story was about a client of Warwick’s who had a very worried horse that she couldn’t seem to get to settle. She described a trail ride (hack) when her horse had spooked at a rabbit, then settled down again. A little later, another rabbit ran past and the horse spooked again, then settled down again. This carried on until rabbit number 13 ran past… the horse flipped, spun round and bolted home!

“How can my horse suddenly think a rabbit is dangerous after 12 rabbits had run past and been perfectly safe?” Warwick explained that we have a finite amount of capacity for worry, he called it the ‘worry cup’. Once this is full, it is full. Whatever tips you (or a horse) over the edge is not relevant, just the fact that there is no more space.

The rabbits are the stresses that are unhelpful. Worrying about making mistakes, being wrong, not being able to make decisions (especially about how much challenge you are happy with), not being supported, not belonging, not being competent; these are all ‘rabbits’. The rabbits collapse your ugly zone reducing the overall challenge levels that you can cope with or even if you enter it at all.

I like this analogy, especially in the context that most of the worry is about not feeling competent, confident or in control. The elements of motivation that are so important to behavioural regulation and learning.

One of the most influential elements of learning is ‘intention’. Genuinely self-motivated engagement changes the way our neural systems behave. Stress shuts that down. A stressed brain cannot learn. It can’t concentrate, can’t remember and isn’t generating new connections and new brain cells. My early paddling experiences were definitely full of rabbits, creating high levels of stress and low levels of self-motivation. I put so much pressure on myself to perform in a learning environment that was motivationally thwarting. The rabbits kept stacking up, leaving less space in the ugly zone and adding to the already downward spiral of becoming less competent, confident and motivated, each time I went out paddling.

Motivationally supportive learning environments not only increase behavioural regulation (we become more self-motivated) they also keep the rabbits at bay. Learning environments that are not needs-supportive result in less engagement, less self-determined motivation, and are breeding grounds for rabbits!

Pooh Sticks

Being overwhelmed – too much information to develop attunement to affordances

On my early kayaking trips I was always following someone on the rivers without a clear goal or focus. Never getting the chance to do the same river section multiple times with purpose and explorative play (repetition without repetition), I became more and more aware of the feeling of ‘winging it.’ I called this Pooh Sticking after the game that Winnie the Pooh and his friends played. They would throw sticks into the water on one side of a bridge and see which stick would reappear on the other side of the bridge first. In my little micro-bat, I basically bobbed to the bottom of the river sections, sometimes even bouncing off rocks and the sides, like one of their sticks in the game. Completely at the mercy of the water and luck.

As with my early paddling experiences, when something is too hard, or there is too much information and we cannot attune to what is important (the specifying information); we are not in the ugly zone, we are Pooh Sticking! This is what I was doing for most of my early paddling and climbing. At best, we can end up as a frustrated novice, with a lack of mastery despite hours of practice. Perhaps even thinking that we are just not talented enough.

Abandoning someone in a full, complex performance environment is likely to result in them Pooh Sticking. The perceptual-motor search space is just too big! Too much information means that it is very hard to identify and attune to the relevant perceptual information. The lack of opportunity for repetition (of outcome) without repetition (of movement pattern) means that the number of opportunities for practice is reduced and the chances of being able to compare and develop adaptive skilfulness are lost.

Summary

We have looked at the first two ‘stages of learning’ in the ugly zone. Engagement and Motivation. The ugly curve combines the energetic constraints (what we might describe as mental skills) of motivation, focus of attention and arousal, with the levels of challenge of our practice environment. It helps us to understand and appreciate how important motivation and intention are for developing creative and adaptive expertise.

Snow, Rabbits and Pooh Sticks are more likely to be found in a learning environment that is not motivationally supportive. Or one that is not representative, or at an inappropriate level of challenge. Now, it is important to remember that we clearly don’t need to have maximum challenge or representativeness at all times when we practise.

Finally, I hope that if you are reading this, nodding along in recognition of these experiences, you have already realised that you may not have been in a supportive learning environment. And that we can change our learning environments when we understand this.

In the next part:

Defining search spaces

The next three stages of learning will be examined (Coordinate, Explore, Exploit), and how they relate to how we structure practice.

Structuring practice for skill development

What is the session goal? What movement problem are you/they trying to solve?

Representative Learning Design (RLD) – The five questions to ask..

1. Is there an opportunity to explore movement variability and solutions?

2. Are the coordination (movement) patterns representative?

3. Is the perceptual information representative (& specifying)?

4. Are the decisions being made representative?

5. Is it a high-validity learning environment?

*It is worth noting that sometimes, especially with horses, we may deliberately use an association to shape a response, then we use classical conditioning to pair the response to a ‘cue’. As with everything in life. There are no absolutes, just principles.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you as always to all of those who help with proofreading and editing. Particular thanks for this one go to Sam Davies, Emma Hathaway, Emma **, Greg Spencer and Jack Wyn-Willimas.

A big thank you to Warwick Schiller for the use of his Worry Cup image.

If you would like some further reading, listening, references or other information. Please drop us an email or fill out the contact us form.