Finding the zone of optimal learning

While watching and listening to skilled performers I have noticed that they all seem to be happy, even passionate, about operating at a level where they are at the edge of their ability. They make mistakes, explore options, try new things and then push a little harder to see what happens. I’ve watched gymnasts, climbers, skaters, and paddlers spend hours, days and even months fervidly working certain moves and problems.

Skilled performers seem to delight in engaging at the edges of their ability; trying, failing, trying again, failing again. Like children playing, they are exploring while they are practising: intently focussed, moving and perceiving, making decisions and problem-solving. All the time they are building on what is necessary for skill development in the context in which they are operating. Their internal dialogue is more “I wonder what will happen if…?” rather than “I must try and do it like this.”

In this article, I develop concepts for understanding what is going on when performers develop their skills through play and exploration. When what they have done in the past starts to break down and they find new solutions beginning to emerge. I look at how grasping the value of performance instability and making mistakes allows us to get beyond traditional ideas of linear progression. This then leads to a way of talking about what happens to skill when we increase the challenge – and to a tool to help us plan and structure our practice.

Embracing the ugly!

We know skill development takes place in doing (in the perception-action workspace) and is not a reflection of what performance may look like at the end of a practice session. Sessions that involve lots of effort and look ugly usually lead to good retention of the learning and transfer to other contexts. Sessions, where performance looks great and effortless at the end, will often result in poor retention and transfer. This is well known and well researched in theories of learning (i.e. the contextual interference-effect). However, this concept is still a challenge to both performers and coaches who have been conditioned to value sessions where the coach gives all the answers and the performance looks much improved at the end.

I have spent a lot of time thinking about what a non-linear learning curve might look like. Humans are complex systems and there are so many variables and so many interactions that it can be hard to identify and make sense of the patterns in the complexity. By incorporating all of the nuanced complexity into one dimension of ‘overall challenge‘ we end up with a pattern (a learning curve) that can help us to design learning environments.

Overall challenge contains all of the constraints that are present and influential to a particular performance situation (individual, task and environmental). Some of these constraints we can influence and change, and some we can’t. Challenge is not just about task complexity and skill level. The overall challenge includes things such as physiological and psychological arousal, perceived support, confidence, resilience, fatigue, speed, power output, consequence, environment and risk.

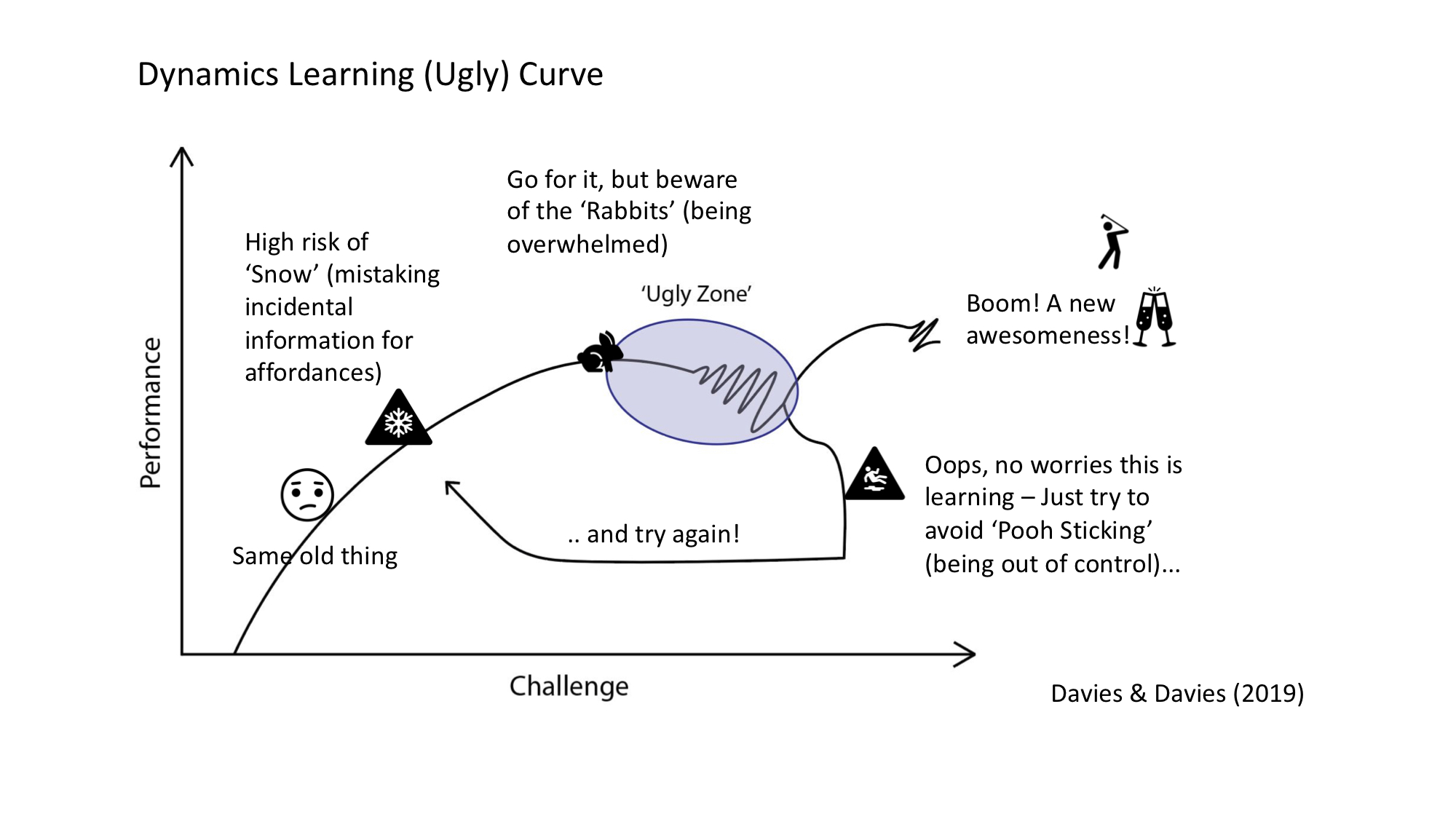

Dynamics Learning (ugly) Curve (Davies and Davies, 2019)

In our model, ‘overall challenge’ is represented by the x-axis. The y-axis represents ‘performance outcome’ and the curve represents the performance solution (for example; a movement or decision-making pattern).

Entering the ugly zone

Now we have a model and curve that reflects our understanding of what we see and which fits with how skill development is understood by everyone from skilled athletes to researchers working within the ecological dynamics theoretical framework. Most importantly, it starts with the idea that when we increase the challenge by changing things we can control, performance starts to become unstable (ugly). This is where learning and performance development gains are made.

To destabilise movement coordination patterns we can adjust things like the required level of balance and agility (for example faster water or a less stable craft for a kayaker or surfer; or a smaller, higher beam for a gymnast to balance on). Other ways we can introduce instability include the increase of speed, power output, movement complexity, consequence or fatigue (for pretty much any sports). A more unusual example would be setting speed or power levels that sit at a movement transition point (for example trotting a horse slowly enough that a walk or piaffe gait [jigging on the spot, to the uninitiated] compete as possible movement patterns for the horse).

If improved decision making and adaptability is the goal of your session, you could set practice tasks where there is more than one possible option for the performer. This would include such things like setting distances that lend themselves to a variety of throwing or kicking solutions, or changing rules, consequences, space and boundaries.

What is important is that changes in patterns of movement, decision-making, perceiving and thinking come from practising at a level where current patterns become destabilised (the ‘metastable state’) developing perception-action coupling in context. Here, all of the necessary elements for performance will eventually be developed (including things like strength, postural tone, perceptual acuity, etc.), allowing new patterns to self-organise and emerge.

What happens when we put the emergence, stabilisation, destabilisation and switching of patterns into a challenge-performance curve? It looks ugly! We get the Dynamics Learning Curve (Davies & Davies, 2019). In this learning curve, Davies and Davies have named the metastable state ‘the ugly zone’. This term was coined by Dr Dave Alred to describe the area just beyond your current ability, where you will try and fail, but try again with support, encouragement, reward, self-esteem and energy. As Dave Alred, beautifully describes in his book, The Pressure Principle,

“Children throw themselves into their ugly zone while they are practically drowning in excitement (to play) and have no fear of failure“.

Building ugly zones

Sometimes we need to build an ugly zone to start with, especially if we are novices or have lost confidence or learnt to fear failure. This can be thought of as a resilience zone. Motivation, supportive relationships and learning environments are recognised as very influential and important. The same applies when we are learning to become a skilful coach. In order to understand how the individual, task and environmental constraints can be adjusted to create an optimal learning experience for different individuals, we coaches need to be able to explore and play in our own ugly zones of coaching practice.

A skilled coach will be able to adjust relevant constraints and move people around in their ugly zone. The old adage of ‘change one thing at a time’ does not hold in a non-linear system. Sometimes many elements will need to be adjusted to allow the successful scaling of one control parameter in a way that gives reliable outcomes for the learner at an appropriate level of challenge. For example, you may need to reduce things like consequence, speed and anxiety in order to increase task complexity. Like a big complicated, non-linear graphic equaliser.

Making ugly zones work – search space and high validity learning

Obviously, there is more to designing great practise than just randomly increasing and decreasing the challenge level. By identifying what is actually limiting our performance, practice sessions can be designed to be more effective. This may entail developing more adaptive movement patterns and decision making, or it could include anything from muscular strength, postural and tonus control, balance, coordination, perceptual acuity or confidence and motivation.

We will look at the concept of ‘search spaces’ and high validity learning environments in the next article: “Snow, Rabbits and Pooh Sticks.” As a coach, defining a search space for someone is a way of setting a challenge instead of giving them the answer you think they may need. Ideally, the challenge is at a level where it is like a good detective story, compelling them to dive into their ugly zone to solve the problem. This fits with Olly Logan’s concept of ‘providing handrails not handcuffs‘. A search space is created and adapted by setting appropriate practice tasks and providing information (for example, giving instructions, demonstrations, and feedback).

The following useful concepts will be explored in more detail:

Snow – when the search space includes incidental information that is easy to perceive and could be mistaken as relevant information (that contains affordances) for perception-action coupling (like mistaking a correlation for causation). This is more likely to happen when practice environments do not offer comparable perceptual cues to performance environments or when there is low practice variability.

Rabbits – when the ugly zone is filled up with things like unnecessary anxiety, stress, fatigue, social pressure and non-supportive environments. These can use up all the ‘play and exploration’ space leaving none for learning.

Pooh Sticking – when we manage to do something, but we don’t know what actually worked. Or we were not in control. This often happens when trying something too far outside of current ability and not being able to pick out the relevant affordances from the rest of the perceptual information. This is also likely to happen where there is a lack of effort, concentration or commitment.

Handrails – information that helps to highlight an aspect of the search space and provide an anchor for the skill we are trying to develop.

Handcuffs – information (usually technical templates) that constrains our learning, disrupts movement exploration and will get in the way of us developing long term adaptive expertise.

Understanding the ugly curve

So, in summary, if we want to change a movement pattern, a way of problem-solving, making decisions or perceiving we need to embrace ugly zones and become comfortable with instability and making mistakes. However, we also need to recognise when confidence and increased performance stability are needed. The ugly curve gives us a way of talking about what happens to skill when we increase the challenge. It highlights the range of the optimal levels of challenge to help us plan and structure our practice.

The ugly zone is the transition to new possibilities. Learning happens when we play and explore in it with focus, effort and passion.

Want to learn more? Look out for the next part by visiting our website https://dynamics-coaching.com/ or our blogs at https://dynamics-coaching.com/our-blog/

Please email for the list of references and recommended reading: marianne@dynamics-coaching.com

Marianne Davies, Sam Davies and Greg Spencer

About the Authors

Marianne Davies; Marianne has been involved in coaching for over 25 years. She has worked mostly with adventure sports, as a coach, coach educator, QA/IV officer, and national trainer. Marianne was the Coaching Manager for Canoe Wales (Paddlesports NGB) for nearly eight years. She has an undergraduate degree in Sport Health & Physical Education, an MRes (distinction) in motivation and learning and is currently doing a PhD with Keith Davids developing models of skill acquisition in equestrian sports coaching. Marianne also runs Dynamics Coaching with her son, Sam.

Sam Davies; After Sam completed an undergraduate degree in geology and geophysics, he studied a Masters’ degree (MSc) in applied sports psychology, under the supervision of Professor Lew Hardy. He is now completing a PhD in human behaviour, creativity and the development of expertise in mineral exploration decision-making.

Greg Spencer has been involved in adventure sport and sports coaching since the 1980s and is Chair of British Canoeing’s Regional Development Team in Yorkshire and Humberside. He has a postgraduate research focus on human development in education and sports coaching and a background spanning from history and anthropology to critical theory and hermeneutics.

Copyright remains with the authors.

Discover more from Dynamics Coaching

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I have read this paper a few times now and it makes more and more sense each time I go back to it. To put that into context, I am exploring/ developing my own paddling skills alongside developing my coaching practise.

Really has reinforced for me ‘playing’ is essential. Plus how both individual and coach practises feed each other. Exciting!

Great article but how is this different from Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development concept?