The exploration of learning and behaviour has led to the emergence of several theoretical frameworks, among which ecological psychology and behaviourism (applied to humans and other animals), and cognitivism (applied to humans only) are prominent. Each of these approaches provides distinct insights into how individuals learn and interact with the world around them, yet they also come with unique strengths and weaknesses. Here I will outline the fundamental differences between these three theories, delving into their key features, criticisms, and the implications for understanding learning processes. My motivations for comparing and exploring these theories are tethered to my desire to understand how humans and other animals (particularly horses and dogs), learn and interact with each other without having to use completely separate and incompatible theories for each species.

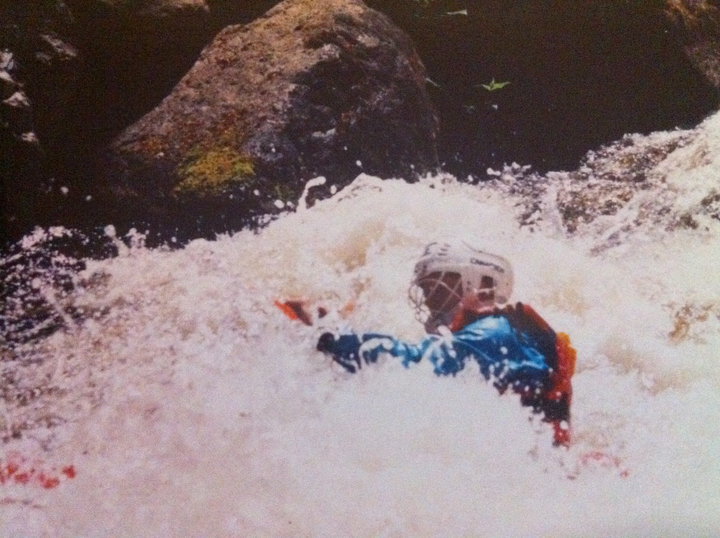

(Cover picture of Marianne working with Skye while training for search and rescue (SARDA) in Scotland).

Behaviourism

Behaviourism is characterised by its focus on observable behaviour and the principle of conditioning, where learning is understood in terms of stimulus-response relationships. This approach operates under the “black box” concept, treating the mind as an opaque entity with little regard for the internal cognitive processes that mediate behaviour. By emphasising external factors, such as reinforcement and punishment, behaviourism seeks to explain learning without delving into the complexities of thoughts, emotions, or motivations. While this can lead to clear, measurable outcomes, behaviourism has been criticised for oversimplifying the learning process and failing to account for the richness of experience.

Limitations of behaviourism

Critics of behaviourism argue that its focus on observable behaviour leads to the “black box” problem, which neglects the internal mental processes that contribute to learning. This can oversimplify experience, as behaviourism tends to reduce learning to mere stimulus-response associations. Additionally, behaviourism struggles to account for the complexities of language acquisition and the generative aspects of language use, as its models do not adequately address the role of cognition and social interactions in language learning. The emphasis on external reinforcement further presents limitations, as behaviours are considered to be performed primarily for rewards rather than for intrinsic understanding or motivation. This perspective also diminishes the recognition of agency.

Cognitivism

Cognitivism emerged as a counter to behaviourism, redirecting focus onto the internal mental processes involved in learning, such as perception, memory, and problem-solving. It likens the mind to a computer, emphasising the processing of information through the manipulation of mental representations and schemas. This approach recognises learning as a complex interplay of thoughts and cognitive strategies, allowing for the possibility of deeper understanding and insight generation.

Cognitive theories introduced significant advancements in understanding phenomena such as language acquisition, and they have fostered an appreciation for the ways in which prior knowledge influences the assimilation of new information. In this regard, cognitivism has provided important frameworks that underscore the active role of learners in shaping their understanding.

Limitations of Cognitivism

Despite its contributions, cognitivism has faced considerable criticism, particularly concerning its reliance on abstract symbols and representations. In our podcast conversation (Part 2. Exploring Learning Theories with David Farrokh: An ecological (systems) approach in practice.) David Farrokh highlights the “symbol grounding problem,” a significant issue wherein cognitivism fails to adequately explain how mental symbols relate to the real world and integrate into actual experiences. This lack of connection makes it challenging to understand how learning and comprehension emerge from purely abstract processing. Moreover, David argues that the deterministic and abstract nature of cognitivist frameworks overlooks the dynamic aspects of behaviour, resulting in a disconnection between cognitive processes and real-world actions.

Cognitivism also tends to neglect the embodied nature of learning, failing to recognise how physical and environmental interactions shape cognitive processes, which limits its applicability to practical learning scenarios. Additionally, the complexity of behaviour is often inadequately addressed within cognitivism, as it can become overly reliant on simplified cognitive models that do not capture the full breadth of human or other species interactions.

Ecological Psychology

Ecological psychology emphasises the dynamic interplay between organisms and their environments, presenting a view of learning that is rooted in the concept of “affordances”, opportunities for action that the environment offers based on an individual’s intentions and capabilities. This perspective encourages a departure from abstract cognitive representations, focusing instead on how individuals actively perceive and interact with their surroundings. Learning is conceptualised not as mere internal processing but as a fluid and situated activity, where understanding is shaped by real-world context and engagement.

A significant advantage of this approach is its consideration of individual agency; learners are seen as active participants who navigate their environments purposefully, adapting their behaviours in response to the myriad affordances they encounter. This provides a holistic view of learning that accounts for environmental, situational, and contextual factors, including the nested influences of different contexts and timeframes on behaviour, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of learning.

Limitations of Ecological Psychology

While ecological psychology offers valuable insights, it also presents certain limitations. The complexity of affordances, which are central to this approach, can lead to ambiguity, as determining which affordances are perceived and how they vary among individuals can be challenging. Moreover, the strong emphasis on context may hinder the establishment of generalisable learning principles applicable across diverse situations, leading to some frustration from those who wish for simple linear rules to supporting learning.

Critics also point out that ecological psychology tends to undervalue internal cognitive processes, which can result in an incomplete perspective on how people mentally conceptualise their interactions with the environment. Furthermore, the qualitative nature of ecological research can complicate efforts to measure and quantify behaviour.

Conclusion

Behaviourism, cognitivism, and ecological psychology each provide unique lenses through which to understand learning and behaviour. A strength of ecological psychology is its focus on real-world interactions and the agency of individuals, presenting a nuanced view that accounts for the dynamic relationships between organisms and their environments. Behaviourism, while historically significant, has faced criticism for its reductive approach to learning, overlooking the organism and the complexity of cognition and emotional factors. On the other hand, cognitivism has contributed significantly to the understanding of internal mental processes but overlooks the environment and grapples with the symbol grounding problem, emphasising abstract representations at the expense of real-world applicability.

As research continues to increase our understanding of both human and other animal learning and behaviour, the more it is evident that other animals are more like us than previously believed. The learning abilities of many other animals, along with the recognition of the implications of evolution, would necessitate that our learning has evolved over millennia and cannot be incompatibly different to that of other animals. Ecological psychology claims to be applicable to all organisms, human and non human. This opens up an opportunity for research to gain a better understanding of learning and skill acquisition in all animals, including multi-species (such as human-horse-dog) interactions.

Bibliography:

Part 2. Exploring Learning Theories with David Farrokh: An ecological (systems) approach in practice. https://www.buzzsprout.com/1975020/episodes/15754250

Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?: Frans de Waal. 2017