Creating an optimal learning environment

Okay, so we know that the satisfaction of basic needs has a positive impact on motivation and will influence whether someone continues to participate. That means we need to make sure that we are able to create an optimal learning environment; what is known as a ‘needs supportive learning environment’6. Autonomy is arguably the most important need and is essential for goal-directed behaviour to become self-determined2. It is unique among the basic psychological needs because a participant (particularly an athlete) could satisfy their need for competence with externally controlled (by a coach) deliberate practice, and they could satisfy the need for relatedness by being part of a team, but autonomy is not as easily satisfied in a traditional coaching environment. This is because the coach makes most of the decisions, and the rules and regulations of a sport can further limit the options that can be given to individual participants.

Autonomy-supportive coaching behaviours

According to Mageau and Vallerand (2003)5, the coach’s autonomy-supportive behaviours directly influence the participant or athlete’s perceptions of competence, autonomy and relatedness.

So, how do we ensure that we are being autonomy supportive in our coaching? Mageau and Vallerand have come up with seven autonomy-supportive coaching behaviours.

- Provide choice within structure, specific rules and limits

- Provide a rationale for tasks and limits

- Acknowledge negative feelings

- Provide opportunities to take initiatives and work independently

- Provide non-controlling competence feedback

- Use non-controlling language, avoid controlling behaviours, and use competition and rewards wisely

- Promote a mastery rather than ego involvement (promote achievement).

Daisy Dewhurst motivated and loving her time Eventing with Ted her horse. Picture by Sarah Braithwaite

- Provide choice within specific rules and limits

Basically, try to give as much choice to your participants as reasonably possible. Obviously, this needs to be within the rules and limitations of the activities and the ability levels of those participating. Having structure is really important. The choices you give need to be well thought out and meaningful so that you do not end up with a learning environment that feels too woolly. You can involve those you work within decisions about types of activities, venues, and progressions. This is usually done for experienced participants having high-level coaching, but less so for beginners where motivational climates can have a greater impact on continued participation. For introductory sessions, look at what choice you can easily give (choice of games, the order of activities (if not progressions), when to progress, the colour of equipment, …). Interestingly, even giving small choices like picking the colour of something, will have a positive impact on motivation. Remember that even choices that are very small and seem insignificant can have a big impact on the perceived need support9.

- Provide a rationale for tasks and limits

By giving simple explanations for why activities are being done you will help your participants to understand and endorse the reasons for doing them. This helps to make the tasks meaningful and they can then be valued and accepted. Think about how you can do this within your activity set up or briefings without them becoming too long and convoluted. Some limitations that may affect your coaching sessions can be overcome by changing your focus; for example, change from running a particular award syllabus to developing competence for their personal goals. Other common limiting factors include venues, environment, kit, and equipment.

- Acknowledge negative feelings

This can be as simple as you letting your participants know that you understand that they may find something boring, or hard to do. That you recognise that they are feeling tired, cold, wet, and a little miserable at that time. This is especially effective when combined with a provision of choice and explanations of the rationale for doing something. Acknowledging negative feelings and stating that there is no choice and you also think it is meaningless, is clearly likely to be less effective! Your ability to relate to your participants is an important part of fulfilling their needs for relatedness.

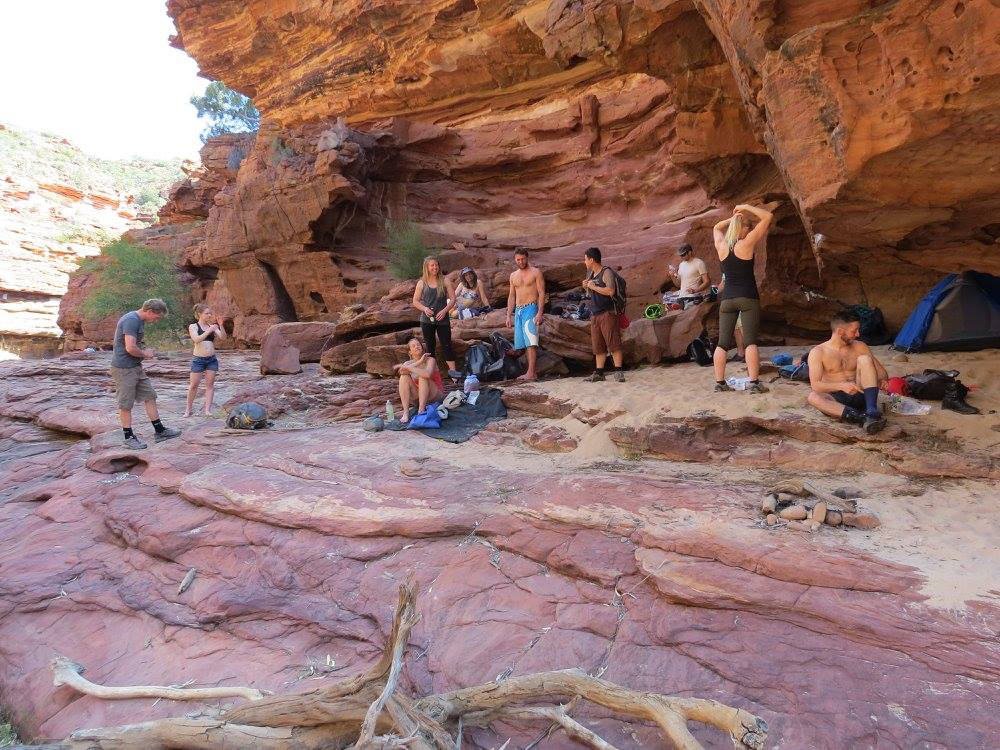

Developing autonomy and strong social relationships during some sport climbing. Photo from Sam Davies.

- Provide opportunities to take initiatives and work independently

This is a big one for me and responsible for much of my negative experiences as a female learner, especially in adventure sports. If you provide support that is not needed or restrict opportunities to take initiatives, be creative, and make decisions; even with the best intentions in mind you will reduce motivation and be perceived as controlling. This behaviour is known as ‘controlling-support’.

Working independently does not necessarily mean working alone. It is also a good way of supporting and promoting social interactions by facilitating the group, peer and pair work. Remember that social interactions are an important part of enhancing the enjoyment of an activity.

- Provide non-controlling competence feedback

There is a strong possibility that up to now you have agreed with most of the autonomy-supportive coaching behaviours we have looked at and that they fit in with what you already do. However, I might be about to suggest some things that do not fit so readily with what you have been told, or you currently do. So please bear with me.

It is important to understand that the feedback you give does not only provide information about an individual’s performance on a specific task but also influences their future expectations and their motivational state. There is a growing body of research that is showing that giving feedback after good performances is much more effective for learning, than giving feedback after poor performances8. This means getting away from seeing feedback as ‘fault finding’ and instead use it to ensure that your participants are aware of when and how to do things well. If they are unable to perform a movement pattern at all, use your ability to change or adjust the constraints (task, environment, individual), rather than give them feedback. This could mean asking them to do something different, adjusting their equipment, changing the environment, or giving them additional information.

There is also growing evidence that the feedback you give can also influence the participant’s expectations of the learning process and how malleable they perceive their performance to be. If you say for example ‘you are a great white water paddler’, this implies a permanence of ability and can be demotivating if performance drops for any reason. If, however, you say ‘those last few break-ins were great’, the focus is on learning and improving, and not a fixed ability. These subtleties of language are particularly important when coaching young children.

A useful way to set up supportive objective feedback is to create opportunities for the participant to ‘self-check’. Setting up skills or tasks in such a way that you allow them to pick up their own objective feedback about their performance from the environment and results. This also helps to promote autonomy and encourages problem solving and exploration of movement patterns.

Finally, like support, feedback can also be perceived as controlling. Saying ‘those last few break-ins were great, as they should be’, is clearly a controlling statement. Again, these are often used with the best intentions, you might be thinking and wanting to convey ‘it should be because you are a great white water paddler’. But, the controlling element here can undermine intrinsic motivation.

- Use non-controlling language, avoid controlling behaviours, and use competition and rewards wisely

There is a lot in here, and like the other points, we are just going to skim through in this article.

Along with competence feedback and support, many behaviours and use of language used can be perceived as controlling. With your coaching language avoid using words and phrases like ‘should’, ‘must’, and ‘have to’, along with phrases like ‘as I would expect’ or ‘as you should have’. It is also very important not to use guilt-inducing criticisms or emotionally laden statements that could be perceived as threatening the relationship between you and your participants. Anything that could be perceived as a threat to withdraw approval, respect or love is particularly damaging.

Thankfully it is generally accepted that controlling language and guilt-inducing statements are unacceptable and undermine autonomy and intrinsic motivation. However, there is still much debate about the use of competition and rewards. Most of the literature in this area agree that whilst competition can increase the intrinsic motivation of those who win, it is detrimental to those who don’t. Also, if you give rewards for participation it can be perceived as implying that the activity is somehow not worth doing for its own sake. If you are coaching children it is worth noting that the detrimental effects of rewards in undermining autonomy and reducing intrinsic motivation are far greater in children than adults5.

- Promote mastery rather than ego involvement (promote achievement)

A mastery climate encourages participants to improve their own skills and judge success by the changes in their own performance. This is influenced hugely by expectations of learning and future competence. We all engage in activities when we have a sense that positive outcomes exist (we will improve), and that we have the agency to achieve them. Conversely, as a coach, if you promote ego involvement you will encourage participants to compare their performance to others. This peer comparison can lead to threats to self-esteem if an individual’s performance is not perceived as good enough2.

Goal setting is a great way to support mastery and achievement orientation. As a coach, it is worth you learning to promote and support the use of effective goal setting. If used skilfully, goal setting can also provide a sense of self-satisfaction, support competence and autonomy, and increase intrinsic motivation. Experience of using and exploring autonomy-supportive coaching activities like ‘self-check’ tasks (see point 5) will also help your participants to goal set and use objective measures adeptly to achieve their goals.

Summary

After a coaching session or any period of practice, any increase in motivation due to the satisfaction of needs support would be advantageous in the long term. Highly skilled movement performance is associated with extended periods of deliberate practice1. Practice conditions that support the motivational transition from less to more, self-determined behaviour, should have positive long term effects and are likely to result in continued engagement in the activity whether for recreation or for performance achievement. This is especially important for groups and individuals who do not feel that they can participate and are not currently regularly engaged in being active.

As a coach, our autonomy-supportive behaviours directly influence participant’s perceptions of competence, autonomy and relatedness. This, in turn, influences their level of intrinsic motivation and self-determined behaviour. An autonomy supportive coach will provide choices where possible, give a rationale for activities and acknowledge the feelings and perspectives of their participants. They will provide opportunities for initiative taking, give non-controlling competence feedback, and communicate using non-controlling language. They will avoid controlling behaviours in the form of physical and psychological control, rewards or promoting ego orientated involvement.

Improved Performance

There is a lot of recent research exploring the effects of needs support and needs satisfaction on performance. The results so far suggest that some of the autonomy-supportive coaching behaviours are associated not only with increased motivation and improved mental health but also with better performance2. That is definitely worth considering for any coach and will be explored in the next article; ‘Motivation part 2: Motivation and Learning’.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Dean (Sid) Sinfield, Sam Davies and Paul Marshall for their excellent proofreading, comments and suggestions.

References:

1 Arkenford. (2014). Watersports Participation Survey 2014 Full Report. Retrieved December 12, 2016, from RYA.org.uk: http://www.rya.org.uk/SiteCollectionDocuments/sportsdevelopment/Watersports_Survey_2014_Executive_Summary.pdf

2 Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Enquiry, 227-268.

3 Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363-406.

4 Jang, R., Reeve, J., & Halusic, M. (2016, January 26). A New Autonomy-Supportive Way of Teaching That Increases Conceptual Learning: Teaching in Students’ Preferred Ways. Journal of Experimental Education, 84(4), 686-701.

5 Mageau, G. A., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). The coach-athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(11), 883-904.

6 Markland, D., & Tobin, V. J. (2010). Need support and behavioural regulations for exercise referral scheme clients: The mediating role of psychological need satisfaction. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11, 91-99.

7 Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living Well: A self-determined theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 139-170.

8 Wulf, G., & Lewthwaite, R. (2016). Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychological Bulletin Review.

9 Wulf, G., Freitas, H. E., & Tandy, R. D. (2014). Choosing to exercise more: Small choices can increase exercise engagement. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 15, 268-271.

10 Website article downloaded on 06.09.17, http://www.sport.wales/news–events/news–events/our-news/latest-news/sport-wales-calls-for-welsh-women-and-girls-to-join-%E2%80%98our-squad%E2%80%99.aspx

Discover more from Dynamics Coaching

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.